“It’s Here. I’m Here. They Were All Here.”

Reflections on Jewish Polish history, the Holocaust, and American Jewish safety

Tuesday was International Holocaust Remembrance Day. I hope you found a moment to commemorate the six million Jews who were murdered. Remembrance is an action we owe the victims.

But if you missed it, it’s not too late (it never is). My man, Phil, recently returned from a heritage trip to Poland. Since he went on an organized Jewish trip, his experience was very different from mine. He was willing to be interviewed about his personal experience, and I thank him for his honesty, vulnerability, and reflections.

Friends: This is one of the most profound Drops I’ve ever published, and I’m not just saying that. Phil’s insights on history and Judaism will surely make you stop and think about our past, as well as our future. It’s difficult to read at times due to its content, but if you care about the Jewish story, and our collective safety, this is a must read. Thank you.

Tell us about the kind of trip you went on, and why you went.

It was a trip run by Pardes, an institution with which I have no affiliation but the rabbi of my synagogue does, and invited people from the shul to join. Frankly, I’ve wanted to go to Poland for a long time. My family is from there, and I’ve always felt connected to that. Ever since I learned about how my great-grandfather came to the United States from Poland growing up, I’ve always wanted to go.

Beyond the family connection, I always felt it was important to see the history of Jewish life there, and to see the camps, to bear witness to what was at one time home to several of the main centers of Jewish life on earth, and where a lot of the version of Judaism that I have received in practice was solidified.

Could you explain further about that, your form of Judaism?

Well, I grew up in a very Ashkenazi environment and the yeshivas I attended were modeled off of the ones that had been formed in Poland and Lithuania. Many of the modern rabbinic figures whose work I studied either came from Poland or Lithuania, or the method that they employed was of Polish or Lithuanian origin.

For instance, we went to the remarkable Jewish cemetery in Warsaw, which I think houses something like 250,000 graves. Two of the graves that are side by side are that of R’ Chaim Volozhiner, who was the founder of the Volozhin Yeshiva, and R’ Chaim Soloveitchik, who taught in that yeshiva and whose work I studied a lot. I didn’t even know that I was going to see their graves, so it was a powerful and meaningful surprise.

Did you learn anything about Polish Jewish life before the Holocaust?

So much. First of all, it’s so varied and grand that it would be difficult to really cover it all. Suffice it to say, Jews lived in Poland for 1,000 years before the Holocaust. There was a rich, vibrant, diverse, and complex history—within the Jewish community, including differences in how various Jewish groups related to one another, and in how Jews interacted with other communities in Poland, including non-Jewish and Christian communities, as well as with the nobility and the peasantry.

The history really illuminates a lot about the role that Jews played in the structure of Polish society at different times, which transformed my perception of Jewish life in America. I grew up with the view of American Jewish life being exceptional, which, in a certain way it is, and always has been. But I suspect a lot of Jews living in Poland at various times probably thought of their lives very much the same way. If they had any sense of history and other parts of the Jewish world, they would have regarded their situation as distinctive if not unique. It makes the story of their end all the more mind-boggling.

The debates we see playing out in the American Jewish community—between religious and secular, liberal and Orthodox, socialists and nationalists, Zionists and assimilationists—were just as active in prewar Poland as they are today. There’s nothing new under the sun.

Where did you learn about this?

We had an excellent tour guide named David Bernstein, a real fountain of knowledge who’s been traveling to Poland since the fall of communism. We packed a lot of notable sites into the short itinerary, staying in Warsaw, Lublin, Lancut, and Krakow, and there was so much to learn everywhere we went it was really just scratching the surface.

I also spent a lot of time at the POLIN Museum in Warsaw, which I have to say is one of the most historically sophisticated museums I’ve ever been to, not just in terms of Jewish museums, but probably of all the museums I’ve ever been to. I highly recommend blocking off a lot of time to spend there. I went three times and still couldn’t get through everything.

I agree. I spent four hours there and needed more time! Let’s shift gears, because I know you visited some camps as well. Can you tell us the ones you went to and describe what that was like?

We went to Majdanek and Auschwitz. Majdanek had been set up primarily as a concentration camp and was later turned into a death camp. It’s in a residential area. There are homes and it’s along a highway, so it really is not in any kind of secluded place. You can see people walking by, and the highway was the same road that German troops used when they invaded Russia in Operation Barbarossa.

Originally conceived as a camp for Russian prisoners of war, there was something strategic about its placement. When Germany invaded Poland, there was a certain antipathy some Poles had for Germans, but certainly for Russians as well. So there was something strategic about the fact that they put a camp for Russian prisoners of war in a neighborhood on the road back from Russia, because it was less likely that any Russian who escaped would find a friendly house to hide in, and it was a way of ensuring that the camp would be secure. The Germans were very clever in a lot of ways, and this is just one example.

We also went to the gas chambers there, and read a story by a woman who was a little girl at the time she was taken to Majdanek. She and her mother were taken into different barracks. It was so crazy seeing how close the gas chambers were to the drop-off points. They could not have been alive for long after they arrived there. So in the story, the girl is looking for her mother. She looks up and sees her older sister-in-law alone. She asks where her mother is, and her sister-in-law says, “She’s not here. I’m your mother now. Do you understand?” It’s impossible to understand the gravity of that sentence.

When we were going into the camps, our tour guide was talking about how the Germans kept the death camps and the gas chambers a secret from everyone. But first and foremost, they wanted to keep the secret from the Jews so that they wouldn’t resist. It’s kind of amazing how capably they engineered that deception even while they were deporting them. Jews were told they were going to be resettled in the east, and they must’ve believed it on some level, or wanted to.

The day we went to Auschwitz it was very foggy, wintry, with snow on the ground. All the stories I had heard about it growing up from survivors were coursing through my mind, particularly the first story I had ever heard about it from my elementary school librarian Mrs. Bodenheim. Right after the tour, I went into the bookstore with the rabbi and bought Rudolf Höess’ autobiography, the camp Commandant, and several other books. It was as though I didn’t know what else to do than buy these books. And the second we walked out of the store I just broke down crying with an abandon I have rarely ever felt. You learn so much about this place, and being there has this indescribable realistic surrealness. It’s here, I’m here, they were all here.

I read some of the autobiography, which he had been forced to write during his imprisonment after the war, when I got home. There are parts where he acknowledges the graveness of what he was involved in. I know a number of people dislike Hannah Arendt for observing what she called “the banality of evil” at the Eichmann trial, but there was something very functionary about some of the people who created and committed the genocide of European Jewry. And reading Höess’ words, you can really see it. He recalls a day when some of the high-ranking Nazis came to see what he was doing, and said that they didn’t envy the brutality of his job. He phrases it as though he was forced to stomach it, as though he experienced it as some kind of burden, as though he didn’t want to do it but had to as a matter of civic duty. But the fact is nobody had to do any of this. It makes you wonder what really made these men different from anyone else, or maybe not so different at all. Terrifying to imagine that any of us, any person, can get caught up in something so depraved if they think it’s justified. I’m not sure there was anything special or different about the Germans or their accomplices across Europe than anyone else in that sense, to be honest. There were people who went along with it, and there were people who didn’t. I think it would be the same everywhere.

And what was also interesting was that I’m quite sure that in the entirety of the trip, Hitler’s name was not mentioned once. It just goes to show how the whole murder machine was operated by so many people. We identify Hitler with the Holocaust but the fact of the matter is, the Holocaust could have happened without him. In a way, it kind of did, because there still is no signed document by Hitler ordering the murder of European Jewry, although we are all quite certain he did order it but avoided a paper trail.

You learn so much about this place, and being there has this indescribable realistic surrealness. It’s here, I’m here, they were all here.

Do you worry about the time when it won’t feel real because it will become distant history?

Oh yeah, I think it’s going to be very difficult to maintain the sense of reality around the Holocaust. It was denied while it was happening and ever since. There has never been a time in history since the Holocaust began that it was not denied by a significant number of people. And that number will probably increase the further away we get from it.

How did being in Poland change the way you think about your own Jewish identity and Jewish life in general today?

As I mentioned before, it sobered my view of American Jewish exceptionalism, and even Israeli Jewish exceptionalism. I love both of those countries tremendously, but these are all experiments in maintaining and transmitting this phenomenon we call Judaism.

And as far as I know, in every physical location where that transmission has occurred, the people doing the transmitting have been violently attacked at some point, meaning Judaism and Jewishness attracts the violent ire of people wherever it is.

Eventually, the people who live around Jews at some point decide that they’ve had enough of them and blame them for their problems. And neither America or Israel are exceptions to that rule. I think it’s important to see that in perspective, that these are really all just experiments in the safe transmission of the national religious and cultural identity that began in an obscure pair of kingdoms at the southwestern edge of the Fertile Crescent.

So do you think the Holocaust could happen in the U.S. today?

Oh 100%. Anything is possible, and the speed at which classic antisemitism has returned to the public discourse is an indication that it’s never hidden for long. I don’t think it would look exactly the same and I don’t know what it would look like, but I think it’s entirely possible. A catastrophic destruction of Jewish life can and has occurred in most places where Jews have lived. Up until a few years ago, Israel was the only place where Jews were regularly killed on the streets, and now it’s become more common throughout the world. Jewish safety and Jewish freedom are not necessarily the same things. But I think just like any people, Jews have a right to both.

And, by the way, Poles murdered Jews before, during, and after the Holocaust as well. But there are signs of light: there were Poles who saved Jews at tremendous risk to themselves and their families. Some of them were murdered along with the Jews they hid. Some are still alive and I think that the Jewish community should do everything they can for them. Their courage and moral clarity in the face of threat should be a lesson to every single person alive. It’s overwhelming to imagine. There’s an organization devoted to them called the Jewish Foundation for the Righteous that readers can check out.

There are good people everywhere and at every time, including Poles today who are deeply committed to recovering Jewish Polish history. We met this one guy in Lublin at the NN Theatre which is doing incredible work documenting the history of Jewish life in Lublin. The guy who runs it is not Jewish and is around my age. He has learned Hebrew and devotes his professional life to restoring and securing the memory of Lublin’s Jewish community. I’m deeply grateful to him and his colleagues.

After having been where the Holocaust actually happened, how do you feel when people invoke Holocaust comparisons to make contemporary political arguments?

I think that the potential for bigotry is something that exists in all of us. That’s a universal lesson from history, not just the Holocaust. But these attempts to equate what’s happening now with the Holocaust are grotesquely and offensively off base, to say the least, and whatever similarities there are reveal the profundity of the difference between them. One can be against the ICE raids, for example, and at the same time recognize how perverse it is to equate them with the mass deportation and murder of European Jewry. What I think is very disturbing is that people who invoke the Holocaust at this moment seem to think they’re learning the lessons of history by imposing the past onto the present. But what they’re doing is the opposite: they are imposing the present onto the past. And that’s like a double act of intellectual violence. I have to believe that when people do it they don’t quite know enough about either situation. It’s an offense born of ignorance, I hope.

What I think is very disturbing is that people who invoke the Holocaust at this moment seem to think they’re learning the lessons of history by imposing the past onto the present. But what they’re doing is the opposite: they are imposing the present onto the past. And that’s like a double act of intellectual violence.

Were you able to find anything about your family while you were there?

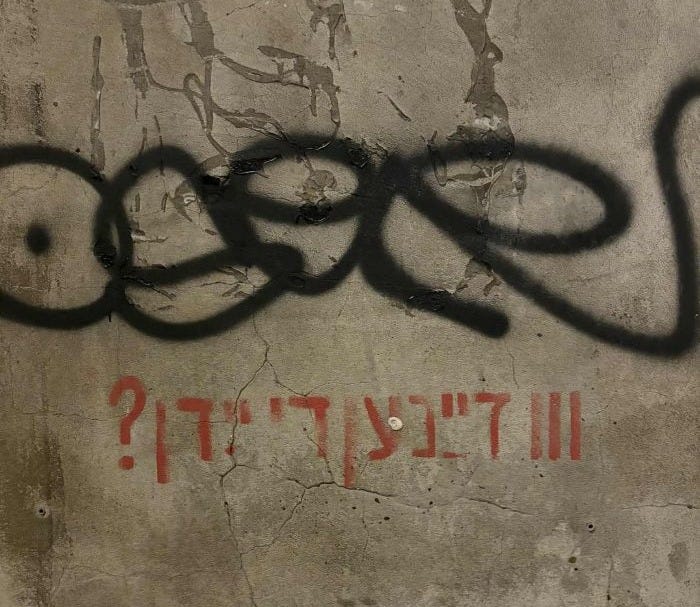

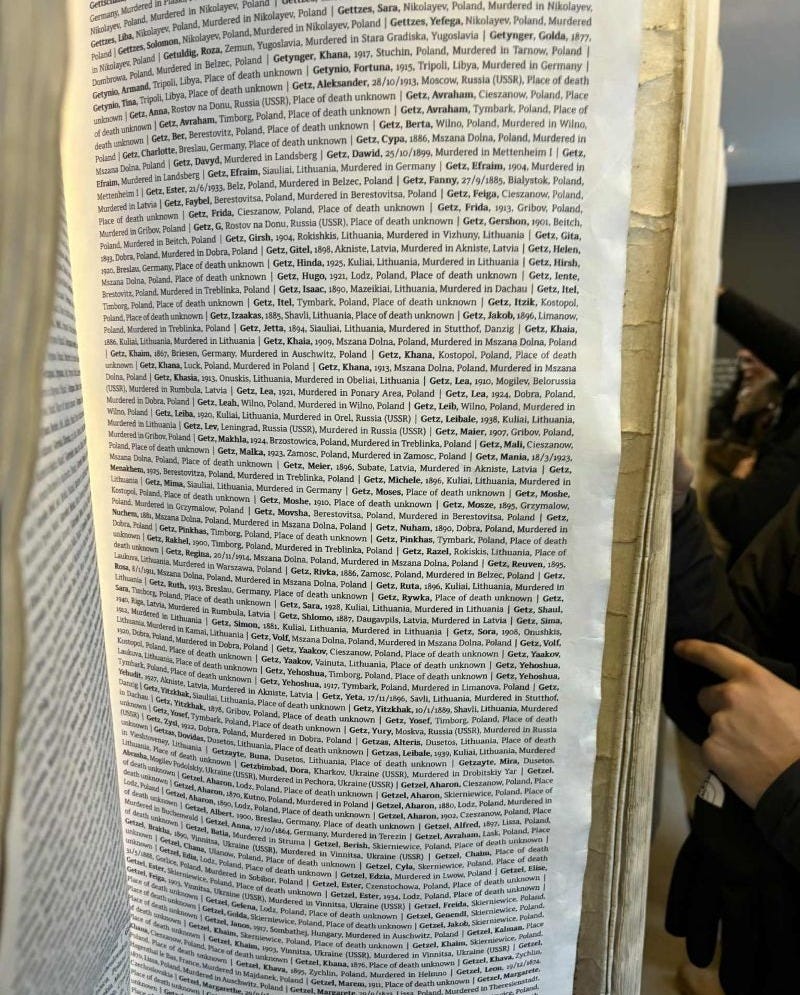

A little bit. I took a photo of the page of victims who share my last name, some who share my great-grandfather’s exact name. I’d rather not say too much about it.

Is there anything else you’d like to share?

I’m very grateful to Pardes, to my tour guide, David Bernstein, and to Rabbi Jonathan Leener who organized the trip for the shul, for the privilege and the honor to learn, and to go on a safe, well-organized trip to the land of my ancestors.

Shabbat plans?

Going to shul with my sweetheart!

Phil Getz is the Managing Editor of SAPIR Journal, which explores the future of the American Jewish community and its intersection with cultural, social, and political issues. You can sign up to receive a free print subscription here.

Miranda again. I want to end this powerful conversation by acknowledging that this Shabbat is the first Shabbat in 120 weeks we don’t have to pray for the return of our hostages.

May we enjoy a sweet and peaceful Shabbat,

Miranda posed the right questions to bring out Philip's keen observations and insightful answers about Polish Jewish history, antisemitism, the Holocaust and current events affecting Jews world wide. He correctly notes how no event today is even remotely comparable to the Holocaust yet so many brazenly make that comparison. I would like to know more about the girl who asked where her mother was, and her sister-in-law who said 'I'm you're mother now." Did they survive? Phil's affirmative answer to the question could it happen here? underscores that exact point made by psychiatrist Douglas Kelley who was assigned to Nazi Hermann Goring as he awaited trial at Nuremberg (see the recent film, the character played by Rami Malek) He wrote a book to support his theory and was shunned the rest of his life. I was privileged to interview Phil's school librarian Hansi Bodenheim for the Shoah Foundation, available to be seen and heard on the Shoah website. Hers is among the 50,000 survivors interviews on the front lines against holocaust denial and distant history.

Thank you, this was really excellent and moving. Thought I'd just put in a few of my reactions/thoughts.

"POLIN Museum in Warsaw"

Just FYI, Professor Sam Kassow was very involved in designing this museum. He has a history course on Ashkenazi Jewish history that I believe you can still watch online through YIVO's website (I watched it several years ago). He is also featured in the documentary about Ringelblum and the Warsaw Ghetto Oyneg Shabbos group called something like Who Will Write Our History (he also wrote a book on them). Finally, saw a great documentary years ago called something like Raise the Roof, about reconstructing the synagogue roof that is in the Polin museum--highly recommended.

"There were people who went along with it, and there were people who didn’t. I think it would be the same everywhere."

Unfortunately the vast majority follow the crowd rather than their own head/moral compass. Those who don't are a tiny statistically insignificant minority (which is not to say they are insignificant, they are truly heroic, only unfortunately there are not enough of them--just look at the current antizionist hate movement today).

"What I think is very disturbing is that people who invoke the Holocaust at this moment seem to think they’re learning the lessons of history by imposing the past onto the present. But what they’re doing is the opposite: they are imposing the present onto the past. And that’s like a double act of intellectual violence. I have to believe that when people do it they don’t quite know enough about either situation."

Thank you, that is so well-put! Unfortunately, it seems much of "Holocaust education" has just given ignorant people more rhetorical tools with which to attack Jews (Dara Horn wrote two excellent articles in the Atlantic about this, both before and after Oct 7).