Spiritual Care Through Connection: A Conversation with Rabbi Ben Varon

A day in the life of a Jewish hospital chaplain

🕯️ This Drop is dedicated to Michael Smuss, the last surviving member of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, who passed away yesterday at the age of 99. He was born in Danzig, Poland, and lived in the ghetto from 1940 until the uprising in 1943. As a member of the Jewish resistance, he bravely fought against Nazis with Molotov cocktails. He survived various death camps and a death march. After the war, he became a painter to process his trauma and later dedicated his life to Holocaust education and dialogue between Germany and Israel. May his memory be a blessing.

I’m excited to share this week’s interview with you all!

I met Rabbi Ben at a monthly salon called “Our Friends Are Smart,” where people share and teach about their interesting jobs in science, technology, art, and more. Shoutout to Adina and Avi for being awesome (and smart) hosts!

It just so happened that the night Ben shared about his meaningful work as a hospital chaplain, the Freakonomics podcast stopped by to record the session!

They were recording an episode about peoples’ jobs, specifically jobs today that didn’t exist in 1940. Even though Ben’s job existed back then, though not as structured as it is today, Freakonomics wanted to record the way in which people talk about what they do for a living. It’s a super interesting episode—check it out here!

I was inspired by Ben’s role at his hospital, primarily because I always associated chaplaincy with Christianity, and I know I’m not alone in that. I enjoyed interviewing him and getting his take on how G-d and prayer play a role in comforting people during tough or vulnerable moments, and how that looks to different people.

It’s a meaningful conversation with an activity at the end. I hope you enjoy it.

Tell us about yourself!

My name is Ben Varon. I am a Conservative rabbi who works as a full-time chaplain at NYU Langone Hospital–Brooklyn, in Sunset Park. I’m a multi-faith chaplain at the hospital. At least 85% of the patients that I work with are not Jewish; I speak and work with people of all faiths, all backgrounds, or no faiths. I’m here to provide emotional and spiritual support to all who need it.

When people think of chaplains, they think of religion or God, but most of our work is about offering emotional and spiritual support. There is a fine line between what is emotional support and what is spiritual support; they often overlap.

For some people who are more religious, they sometimes reflect on their faith, asking, “Why is God doing this to me? Why is God punishing me?” Those existential questions do come up, but they tend to be the minority.

Most of the time, people want someone to sit and talk with them and help them process what they’re going through. Prayer might be a part of that. Patients are going through really hard things, whether it’s end of life or not, or a diagnosis they just received. Being in the hospital, no matter what people are going through, brings up feelings. They reflect on their life, on what they’re going through, on their family or relationships, on everything and anything that could come up for someone. We as chaplains try to provide a space for them to reflect on what they’re going through.

What does a typical day look like?

Every day looks different. When I arrive, my first focus is on spiritual care consults. In an ideal world, most of my day would be spent on these, since consults come from doctors, nurses, social workers—anyone in the hospital who can refer us. With 500 patient beds, we can’t see everyone, so referrals help us reach those who need us most: patients facing a tough diagnosis, someone in distress, or a family member struggling.

The second focus of the day is the palliative care list, which is helping patients and their family face serious illness and end of life with dignity and peace. This includes checking in with patients if they’re able, but if they’re not able to, then I check in with their family on how we can support them during this process.

The third area is responding to every cardiac arrest and trauma 1, and we try to go to every rapid response. In these cases, we’re going to see if there’s family present. For the most part, the doctors and the medical team are with the patient, so we’re not there to support them at that moment—maybe afterwards or a day later when they’re more stable. But in that moment it’s to see if there’s family there.

And then after that, it’s making rounds on the units that I cover. I cover about five units, and I try to find the people that might need support. Sometimes I look at the hematology/oncology list. Other times I’ll look at a patient’s age. I make a point of being seen by staff—nurses, physical and occupational therapists, social workers—since chaplains aren’t always top of mind. Often, being present leads to moments like a nurse saying, “Chaplain, I think this patient could benefit from your support.”

Tell us about your rabbinical journey.

I finished rabbinical school a little over three years ago. I never had any interest in being a pulpit rabbi. I thought Hillel work on a college campus would interest me. I applied to a few college Hillels, but it wasn’t the right fit. My last summer before graduating was when I did my first unit of chaplaincy work, coincidentally at the hospital that I work at now. I liked the experience enough that I wanted to then apply for a chaplain residency in my last year. The year right after rabbinical school, I did the residency and that’s what really sold the work for me. I did the residency for a full year at New York Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital in Park Slope. A few months after that ended, I got a full-time job here at NYU and I’ve been ever since.

How has rabbinical school helped you in your current work?

I loved my time in rabbinical school. I learned a lot, and I grew a lot as a person. We talked about using our spiritual authority, and a lot of that takes confidence and belief at the beginning of rabbinical school. But it took time—about five years in rabbinical school and the year of residency—to develop belief in myself, belief in what it means to be a rabbi and to not be afraid to use that authority. At the beginning of the residency, I was more hesitant to put myself out there or put myself into a tough situation. The more I’ve done the chaplaincy work and leaned into what it means to be a rabbi, the more I can go up to a doctor and say, “This is what we do, and what we offer is important.” So much is focused on the physical, so how do we try to say the emotional and the spiritual are integral to a patient’s wellbeing?

How has your work shaped your beliefs in G-d?

The role that God plays in my work is something that I’ve always struggled with. On one hand, belief in God or not doesn’t impact the work that I do. How I practice Judaism doesn’t impact who I am or the work that I do. It’s not at the forefront of why I do what I do.

And at the same time, I want to believe that God is in human interaction. It’s when we see godliness and value in each other. That’s being made in the image of God. I see it the most when I’m praying with patients, when I’m holding a patient’s hand, when I’m sitting with them in silence, being with them, supporting them. I like to believe that’s where God is.

How about prayer? What role does that have in your work?

Prayer can play a powerful role in my work, though it looks different for each patient. For some, especially my Christian patients for whom spontaneous, outloud prayer is a part of their faith, it’s how they connect with God. When I sit with patients, I try to craft a spontaneous prayer that acknowledges what they’re going through, letting them know I see and hear them. Even if my own beliefs differ, I act as a vessel, supporting them in communicating with a higher power in a way that feels authentic to them. I typically start with “Please God,” and leave space for patients to conclude in their own faith language, like using Jesus’ name.

Prayer helps patients feel less alone—not just physically, since I’m present with them, but also spiritually, reaching out for support, healing, or protection. One of the hardest parts of being in the hospital, for many patients, is the loneliness, whether someone has little family support or even when loved ones are present but can’t fully understand their experience. Prayer allows them to feel the presence of something higher, listening and protecting, providing comfort and connection when human support alone can’t fully meet their needs.

How do you take care of your own mental health?

This is the question I get most. I don’t have a great answer other than I think I’m just made to do this work. In an ideal world, we’re all able to find the work that suits us and this just happens to be work that suits me.

A couple of years ago during my residency, the mom of a young patient I had supported said to me, “I don’t know how you do this every day.” And what I said to her was, “I’m not going through what you are going through.”

That doesn’t mean it doesn’t take a toll on me. And maybe it’s taking a toll on me subconsciously, but thankfully I am able to not take it home with me. It doesn’t mean I don’t have my moments when I need to cry, or talk to family and friends and staff that I’ve built really good relationships with.

Is there anything else you’d like to add?

I lead a weekly spirituality group in the hospital’s behavioral health unit. This work is similar to other chaplaincy but requires different skills. One of the things I love about group work is helping people realize they’re not alone—others in the room may be facing similar struggles, and supporting each other can be incredibly healing.

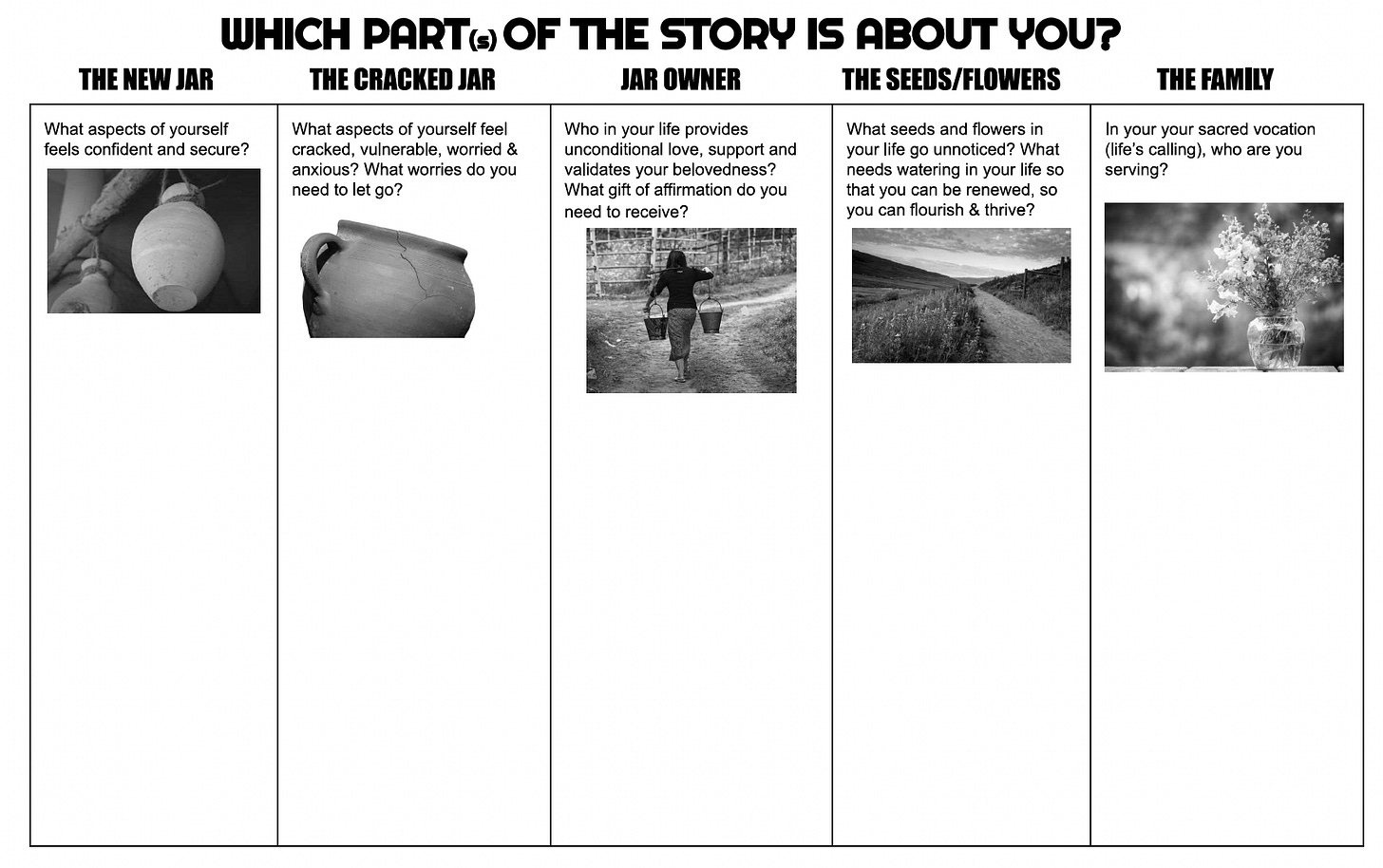

A lot of what we try to do in the groups is help people identify what is spiritual for them, whether it’s God, faith, religion, nature, their family, or something else.

The definition we use for spirituality is the things in life that give us meaning, purpose, and connection to something larger than ourselves. Again, that can be your faith or religion, but I like to say it could be baking, fishing, or going to concerts. What might be spiritual for one person might not be considered spiritual for someone else. When I lead these groups, my role is to help participants identify what supports, guides, or protects them in their lives.

I use the following story and activity to help patients explore this:

What are your Shabbat plans this week?

I am eating Shabbat dinner at my friend’s apartment, going to synagogue Saturday morning, and relaxing on Shabbat afternoon.

May your Shabbos be flood free,

P.S. Join next book club on Zoom THIS Sunday, 10/26 to discuss As a Jew by Sarah Hurwitz!

Download the Cracked Jar story and activity here: