Kosher reindeer, anyone?

An exclusive look inside the Helsinki Jewish community in Finland.

Hyvää huomenta! (good morning in Finnish)

Helsinki: land of saunas, salmon soup, silence, and… Semites? More specifically, Jews? Yep, Jews have been living in Finland since the 1700s, and today there are about 1,800 Jewish residents, most of whom live in the capital of Helsinki, and a couple hundred living in Turku, a small coastal town in the southwest.

The History

A small group of Jews came to Finland in the 18th century while it was under Swedish rule and were subjugated to living in three towns – all of them outside the territory that is now modern-day Finland – declared by a law called Judereglementet (‘The Jewish Regulations’).

The Finnish Jewish community really began when Jews arrived as Russian soldiers called cantonists who were conscripted to fight for the Imperial Russian army for 25 years after finishing their studies. Between 1809–1917, Finland was under the rule of the Russian Empire. Many of these soldiers remained in Finland in the 19th century after their military service ended, working as tradesmen and craftsmen, often living in the last place they had been stationed.

At this time, there were no Jewish brides there, and the local Jews asked matchmakers from the Pale of Settlement to help them find wives. In the absence of railways, unmarried girls and widows were transported by horse-driven cart. When former cantonists were asked how they met their wife, they would reply, “I got her from a cart.” Sounds so much easier than swiping, TBH.

It wasn’t until after Finland declared independence in 1917 that Jews were granted full rights as Finnish citizens. There is a small Jewish cemetery in Hamina, the town where the first Jew, Jacob Weikam, settled and is dedicated to Jewish soldiers who served in the army of the Russian Empire.

World War II

Finland’s role in WWII was complex, involving a relationship with Nazi Germany not because of aligned ideologies, but for security concerning the Soviet Union and preserving Finnish national identity.

Despite being an ally of Nazi Germany, Finland largely protected its Jewish population and resisted German pressure to implement antisemitic policies. The Finnish Jewish community played a crucial role in supporting the Finnish war effort, with many Jews serving in the military and contributing to various aspects of society. However, there were cases of discrimination and antisemitic sentiment within Finland, including some incidents of harassment and the confiscation of Jewish-owned property.

327 Finnish Jews fought for Finland during the war, of which 15 were killed in action in the Winter War of 1939 when Russia tried to gain territory, and 8 in the Continuation War of 1941, when Finland joined forces with Germany to regain the territories it had lost.

These Finnish soldiers maintained their Jewish identity while fighting against the Soviets, creating a makeshift synagogue near the front lines, with a Torah imported from Helsinki. The Finnish High Command granted leave to Jewish soldiers on Saturdays and Jewish holidays. Worshippers prayed together much to the Germans’ chagrin.

Lazar Raskin, a Soviet Jewish prisoner of war captured by Finnish troops, shared his reaction to meeting Finnish Jewish soldiers in a prisoner camp in the Russian magazine, Lechaim, in 2005:

“In spring 1943 we were informed that several Finnish Jews were coming to our camp. We were extremely surprised because we did not think that there were Jews in Finland and that they were free to come and go. Three elderly men came and introduced themselves as representatives of the Helsinki Jewish community. They brought boxes with matzoth and told us that Passover was imminent . . . They also brought books, including stories by Shalom Aleichem and I. L. Peretz and The History of the Jews by the famous historian S. Dubnov (all in Yiddish).

In the evening after work we spent time with our visitors. We felt at ease with them and had a friendly chat in Yiddish. Just the fact that we saw Jews before us, safe and prosperous, made it a festive occasion. We knew what the Nazis were doing to European Jewry. The visitors told us that the Finnish authorities, despite the demands of the Germans, not only did not persecute the Jews but even defended their interests. Later we sang Jewish songs together. Surprisingly, the Finnish Jews knew the same songs as we did.

. . . The visit left a pleasant impression and we remembered it for a long time. The most precious presents were the books. Because very few people could read Yiddish I read aloud the stories of Shalom Aleichem and everybody laughed. I studied The History of the Jews very thoroughly and later gave several lectures on this theme. Everybody listened very attentively because for most of us the history of our people was absolutely unknown.”

Post-WWII, 28 Finnish-Jewish veterans joined Israel in the War of Independence in 1948, and Finland donated weapons to help the cause, representing the highest per-capita participation of any diaspora Jewish community.

The history of Jewish Finnish soldiers is a complex one. The veterans were seen as collaborators who fought for the Germans, while some saw them as just fighting for a common enemy, the Russians. After the war, Finland was not held accountable for the Holocaust or its role in supporting Nazi Germany, as it was officially considered a co-belligerent rather than an ally.

Jewish Finland Today

Today, Finland's Jewish community of about 1,800 (of whom 1,400 live in Helsinki) continues to thrive.

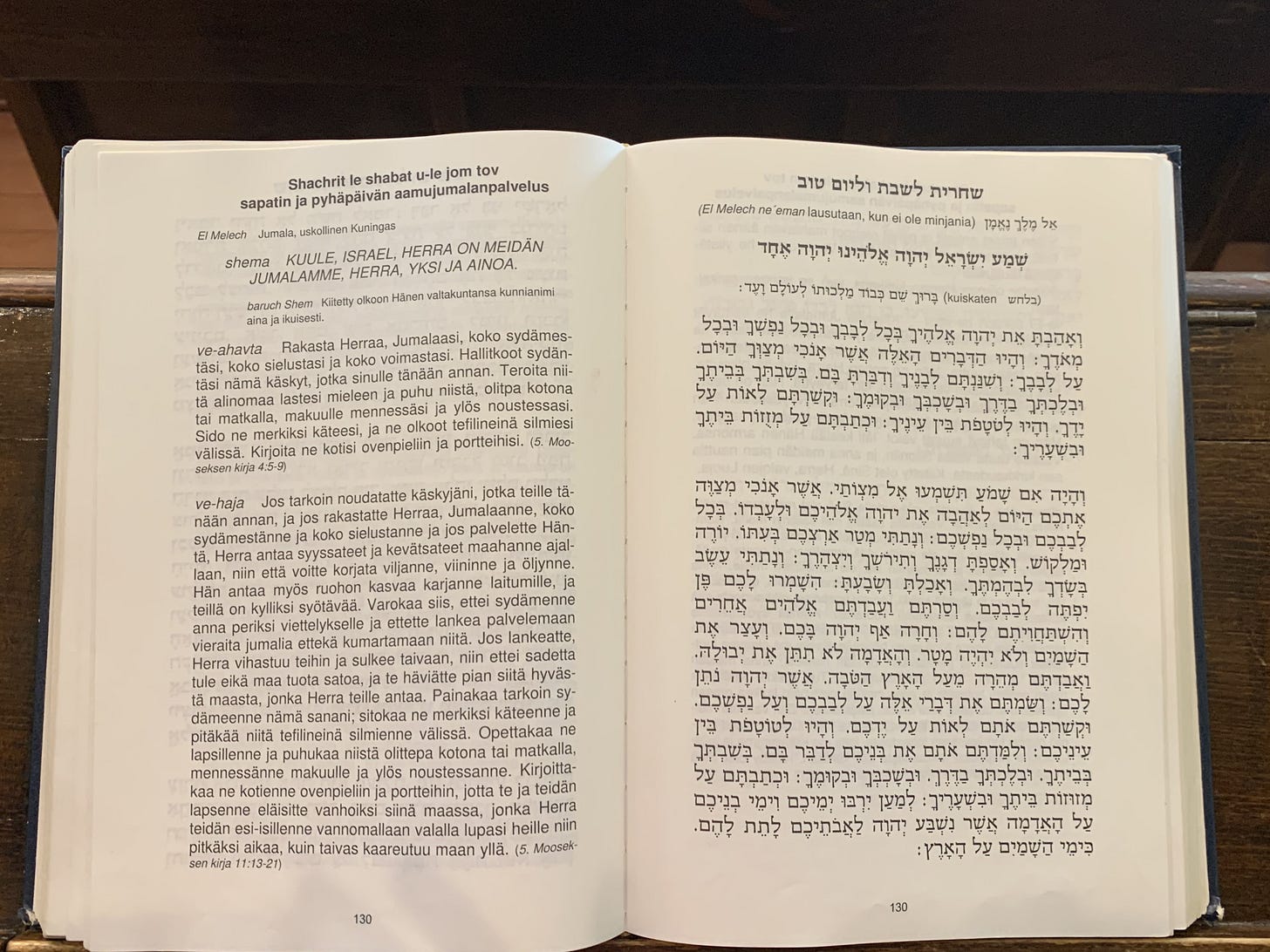

I visited the Jewish Community Center, synagogue, and schools in Helsinki. In 1900, the city of Helsinki gave a plot to the Jewish community on which to build a synagogue. The area had been settled by Jews who sold clothing in the nearby market at a time when a quarter of stores were owned by Jews. They were still seen as the “other” though, often speaking Yiddish. The Orthodox synagogue was built in 1906 and is still in use today as one of the two synagogues in the country. There is also a Chabad downtown.

Jews have integrated well into society in the modern era, holding all different types of jobs as scientists, painters, musicians, and authors. There is one Jewish member of parliament in Finland who has been in office since 1979.

It’s relatively easy to keep kosher in Finland. You can buy kosher meat at the K-Supermarket, and there is even reindeer prepared in a kosher way, though that is hard to come by. Luckily, fish is the food to eat in Finland, and you can buy any raw fish that has fins and scales.

I then visited the school, which teaches grades 1-9, and the kindergarten. I was impressed by the low cost of tuition, as long as the child’s Jewish parent/s is a member of the community, especially compared to the tuition of non-Jewish private schools in Helsinki and that in the U.S.

As someone who works in Jewish education, I was curious to see if the Finnish Jewish community faces similar challenges as the American one, like shortage of teachers, lack of funding, and decreased school enrollment. To gain insight, I tried speaking to the kindergarten teacher about it, but she said they had everything they need, from funding to materials. I realized her education is on a much smaller scale, though.

A volunteer in the community shared her perspective about the disconnect between current students and the education they’re receiving. The school is run by the religious community, and most of the students are raised in secular homes, so what they’re learning might not always connect with them. This really spoke to me because I am a firm believer of meeting people where they’re at. Like, you can’t teach Pirkei Avot (ethics) to someone who is still trying to learn how and when to light Shabbos candles. Trust me!

To gain some more insight, I spoke to a teacher from the grade school, who shared the same sentiments of that religious disconnect. It's worth mentioning that since the school is a municipal school run by the government, the teachers are not able to explicitly promote the religious aspects of Judaism. The teacher shared that you can have a conversation with your students about what or who Gd is, but you can’t say, “As a Jew, thou shalt obey His commandments.”

There is also the issue of intermarriage, which is a detriment to any Jewish community because it causes a decline in continuity. From her perspective, the volunteer shared that some heads of the community aren’t accepting toward some patrilineal Jews or may not have had the level of conversion to their liking.

Learning of this bias upset many of my fellow Jewish travelers because they saw it as self-sabotage for the growth of the Jewish community. I have mixed feelings about this as I continue to learn in a Modern Orthodox setting, where I am more exposed to the belief that Judaism is passed down matrilineally. But this debate is for a whole other Shabbat Drop!

Either way, meeting the Jewish community of Helsinki really opened my eyes to the nuances of Jewish education and the challenges one might face when building a Jewish collective. And we got to play with some of the kids from the grade school and eat delicious Israeli food!

Time for some Finnish Yiddish! Jac Weinstein (1883-1976) was a Helsinki-born Yiddish playwright and impresario. His songs had been rediscovered, pieces that were mainly performed by the Idishe dramatishe gezelshaft in Helsingfors (Jewish Dramatic Society in Helsinki) which Weinstein established in 1922.

The Helsinki Yiddish Cabaret, a collaboration by Finnish Yiddish scholar Simo Muir, Yiddish vocalist Sasha Lurje from Latvia, and American singer Lorin Sklamberg, not only brings Weinstein’s tunes to life, but also educates about Finnish Jewry. Enjoy.

Shabbat Shalom! What are your plans?

So grateful to have experienced this community & all of its complexities with you!

-Hannah

Loves this article! I learned so much. I visited Helsinki 2 years ago and really loved it. I had no idea there was a Jewish school there! Thanks for the share.